Understanding Circumcision in the Bible

Circumcision is a prominent theme in both the Old and New Testaments. Many Christians have not given much thought to the significance behind circumcision. Why were Israelites circumcised? Although circumcision was practiced by other cultures and religions, it holds a special value for the Israelites. In this article, we will explore the reasons behind this ancient practice of circumcision and what it meant for the Old Testament Israelites.

Circumcision and the Egyptians

Although we know about circumcision primarily through the Old Testament description, it was not a unique custom known only to Israel. Jeremiah 9:25–26 provides a list of nations that seem to have practiced circumcision. Besides Judah, this list specifies Egypt, Edom, the sons of Ammon, and Moab. Out of all the nations listed, Abraham appears to have had the most significant interactions with Egypt. He spent time in Egypt during a severe famine in Canaan (Gen 12:10–20) and at least 23 years with Hagar, an Egyptian maidservant (Gen 16:1–3; 17:25). In the time after Abraham, Israel spent over 400 years in Egypt where they developed as a nation and continued to practice the rite of circumcision, apparently unaltered (cf. Exod 4:24–26; 12:44, 48; Lev 12:3; Josh 5:2–9). Although Scripture is silent on the issue, it seems reasonable that when God instituted the sign of circumcision with Abraham, he interpreted circumcision in light of his familiarity with Egypt.

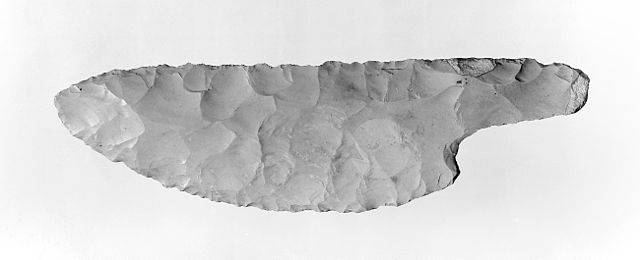

Egyptian circumcision differed from Israelite circumcision in a variety of ways. First, Egyptian circumcision involved only a slight incision in the foreskin, rather than a removal of the entire foreskin as practiced by Israel. Second, the Egyptians performed circumcision on males 6–14 years old, rather than on male infants eight days old. Third, the evidence seems to indicate that circumcision was obligatory for only the rulers and priests of Egypt, but in Israel it was required for every male Israelite (Gen 17:10). After presenting and evaluating the Egyptian evidence, Meade concludes, “Egyptian circumcision functioned as a specific, voluntary, and initiatory rite to identify and affiliate the subject with the deity and to signify devotion to the same deity” (Meade, 45).

Given the above information, I believe we can reasonably establish the purpose of Egyptian circumcision. Since Egyptian circumcision focused primarily on the royal and priestly class, it seems correct to understand Egyptian circumcision as some sort of divine dedication of royalty or priests. If Israel was aware of the dedicatory implications of the Egyptian rite of circumcision for the royal and priestly class, then it would be natural to associate the sign of circumcision with the role of being a kingdom of priests. The title “kingdom of priests” is exactly how God labels Israel in Exodus 19:6. If this understanding is correct, circumcision would at least be marking Israel out for a special role as a kingdom of priests. But it is unlikely that this nuance exhausts the full meaning of circumcision for the ancient Israelites.

The Context of Biblical Circumcision

In addition to the likely Ancient Near Eastern background of Egyptian circumcision, Scripture itself provides a helpful description that allows us to discern the meaning and significance of circumcision. Genesis 17 is the initial mention of circumcision in the Bible, and the context of the sign of circumcision is God’s promise of an eternal covenant (Gen 17:7, 13, 19). Importantly, Genesis 17 was not the initiation of the covenant. God had already initiated and instituted His covenant with Abraham previously (cf. Gen 12:1–3, 7; 13:14–17; 15:7–21). As part of the covenant, God had promised Abraham blessing, descendants, land, nations, and kings. Circumcision was a sign that was tied to these promises of the Abrahamic covenant.

How Signs Work in the Old Testament

A sign in the Old Testament can function in three different ways. First, a proof sign endeavors to prove a proposition through extraordinary display. An example of this would be Isaiah 38, where God promises Hezekiah that He will add 15 years to his life (in response to his repentance), as well as deliver Jerusalem from the king of Assyria. To prove that this prophecy would occur, the prophet Isaiah says God will give a sign, specifically, the sundial will turn back ten steps (vv. 7–8). Second, a symbol sign represents something through association or similarity. An example of this is when Ezekiel sets up a model of Jerusalem under siege using a brick and an iron griddle, which is called “a sign for the house of Israel” (Ezek 4:1–3). Finally, there can also be a cognition sign, the purpose of which is to bring to remembrance something in the mind of an observer. One can further subdivide a cognition sign into two categories: identity signs, which mark something as having a specific identity or function, and mnemonic signs, which bring to mind something already known. An example of an identity sign would be the banners of Numbers 2:2, which each tribe would fly to identify the encampments. Although the ESV translates this word as “banners,” the Hebrew word simply means signs. An example of a mnemonic sign is Exodus 13:9, where the eating of unleavened bread is a sign which reminds Israel of the Exodus experience and how God brought them out of Egypt.

In light of the above categories, how is the sign of circumcision functioning within the Abrahamic covenant? To answer this question, some scholars point to similarities in Genesis 9:8–17, where the rainbow functions as a mnemonic sign to remind God of His covenant between the creation and Creator. The rainbow reminds God that He will never again destroy the world by flood (vv. 15–16). If the sign of circumcision is like the sign of the rainbow, then the sign of circumcision could be a reminder to God to be faithful to His covenant with Abraham to make his descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky (Gen 15:5).

However, although there are a few parallels with the Noahic covenant, Genesis 17 does not indicate that the sign of the covenant is to remind God of anything. Thus, it is conjecture to say that the sign of circumcision is to remind God of something. Moreover, in contrast to the Noahic covenant, there are significant obligations placed upon Abraham to walk blamelessly (v. 2). As such, although it is possible that the sign of the covenant reminds God of His promises, it seems more in line with the context of Genesis 17 and the command to be blameless that the sign would remind Abraham and his descendants of the need to live holy and righteous lives before God as His chosen people in light of His promises. This emphasis would seem to coincide with the Egyptian concept of circumcision being a mark of dedication and commitment to a deity.

Putting it All Together

Within the context of Genesis 17, circumcision as a mark of dedication and commitment to God makes sense. However, there are later texts where this idea of dedication and commitment to God do not seem to be the best understanding of circumcision. When we look further into the Old Testament, we regularly see the idea of uncircumcision being used as a figurative depiction of ineffective body parts. The best example of this is probably Exodus 6:12 where Moses wonders how Pharaoh would listen to him, because he was of “uncircumcised lips.” This description most likely parallels Moses’s previous complaint in Exodus 4:10, where Moses claimed he was “slow of speech and of tongue.” Hence, the significance of the phrase “uncircumcised lips” most likely refers to a lack of ability.

That uncircumcision refers to inability seems supported by how Scripture writers use the language of uncircumcision to refer to other body parts as well. For example, Jeremiah 6:10 says that the people of Israel had ears that were uncircumcised, and therefore “they cannot listen.” The picture is one of having skin over the ears, and therefore the ears are incapable of hearing. Like Exodus 6, this illustration of uncircumcision seems to indicate inability. Similarly, elsewhere Scripture refers to an uncircumcised heart as a metaphor for a dull, insensitive heart (cf. Deut 10:16; 30:6; Jer 4:4; 9:25). Leviticus 26:41 notes that the solution to an uncircumcised heart is humility and turning from iniquity. All of these examples seem to be consistent with the idea that language of uncircumcision emphasizes the inability to function as one ought to.

In summary, circumcision likely was a visible reminder to Israel of their special, holy status before God. They were to function as a kingdom of priests to the watching nations. Additionally, circumcision was a reminder of God’s promises to Abraham—namely, a multitude of descendants, nations, kings, land, and blessing. Due to the prevalence of circumcision in Israelite society, uncircumcision became a ready illustration of dysfunction and inability. Prophets regularly referred to mouths, ears, and hearts as uncircumcised in order to describe a failure to function properly.

For Further Research

John D. Meade, “The Meaning of Circumcision in Israel: A Proposal for a Transfer of Rite from Egypt to Israel,” Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 20, no. 1 (2016): 35–54.

Michael V. Fox, “The Sign of the Covenant: Circumcision in the Light of the Priestly ʾôt Etiologies,” Revue Biblique 81 (1974): 562–69.

2 Comments

Ghost Writer

Hello Peter,

I find your articles really good to read, they show a lot of knowledge and research. I found you recently, and always try to learn from people, get new perspective on things I might not fully understand or maybe I never cared to research.

Especially about Old Testament, I read it, but I usually focus on New Testament.

I have had my question about circumcision for some years, I have never really asked anyone, because in a way I care but I don’t care or really have anyone to ask.

I am surprised you only used only Old Testament scriptures to talk about it here, it makes sense but why I wonder about the circumcision has to do with Paul, and I already saw and read “Paul was (sometimes) against Circumcision”, but still not the same, of course this one is better to read, and gives nice information about other cultures, which puts more questions in my head as I was reading it.

But anyway, the story is once I was reading New Testament in order, I read my bible in Spanish and English and there was one verse that caught my attention in Spanish, because it is not clear, but it caught my attention the wording used there. so I went and found the English version and the translation seemed to say it cleared in the way I understood the Spanish version.

After that, I always think about this specific verse and how it made me question so much, it is so short. The problem is reading Paul words, how he talks about circumcision , it all seems just strange?

Anyway I am talking about 1 Corinthians 7:18(-20)

The way Spanish translates it is “18 ¿Fue llamado alguno siendo circunciso? Quédese circunciso.”

NKJV: “18 Was anyone called while circumcised? Let him not become uncircumcised. ”

KJV: “18 Is any man called being circumcised? let him not become uncircumcised. ”

NIV: “18 Was a man already circumcised when he was called? He should not become uncircumcised. ”

The NET: even go and says “18 Was anyone called after he had been circumcised? He should not try to undo his circumcision.”

Anyway it should be clear why my questions about it.

The thing is, we are talking about Paul letters, while Paul was cool and all, he didn’t go around like Jesus who was talking in code like Jesus parables; Paul was writing letters, so people would understand his words clear and simple, so it is weird to think he would use some sort of code and metaphors in this specific issue, yes, he used “circumcision of the heart” just like you pointed out many used it for other parts of the body.

But why would he say “not become uncircumcised”, like if that was possible? You can technically become circumcised but not the other way around, and since he is talking about being “called called” like, you were a ‘Jew under the law but now you want to follow Jesus so that’s all that matters now’ then, why did he phrase it like that?

And the problem is if you read Paul, and as pointed by your “Paul was (sometimes) against Circumcision”, it happened, but, how did some Jew knew who was circumcised or not? I mean, how will anyone know in today’s work that information, let alone 2000 years ago.

Were people showing their ‘parts’ to other men just like that? Because even today, that’s the only way to know it, someone can say “I am circumcised”, and you can’t be sure.

If someone had to sign like a paper “this person was circumcised”, why would you get circumcised if you can just forfeit the document? since only looking at your ‘part’ would really say if you are or not.

You can see repeatedly: “This one was circumcised”, “this other wasn’t”, “this one had to be circumcised”, “be careful they find out you aren’t”, how did anyone know they were or not? It would be weird to image, the only way to fullfil the law would be to show the most private part in humans you can imagine, unless it was a way to shame them, rather than be a ‘promise’.

And your talk about Egyptians circumcision, makes it more interesting, because it seems their methods were less ritualistic than Hebrew people….?

Well today, I have read that adults just need to see a drop of blood to be considered circumcised, so it is only the babies being punished with it.

But one thing always confuses me, God made us to his image, yet, his ways were “well now you need to mutilate part of you beautiful body which is made to my image as a covenant”?

There are many issues with circumcision, for example, circumcised people will be more sensitive to pain, of course, this is not a perfect science but all people I know that have said they are circumcised, seem not to tolerate pain, and then we can think about the traumas the children goes through when that happens, even if ‘it’s just a baby, won’t remember it’.

I mean, if God, said cut your arm, your ear, your leg, will that makes sense? I mean, it’s kind of weird to thin God will command such thing, because we have to think the way the people who call themselves ‘Jews’ do it today do it.

When I think about how the devil works, I can see devil ways are about mutilating people or non-Hebrew God, as you say Egyptians do it, then still African tribes today do it to women and other cultures too, but we have cases today, with the whole gender agenda and transgenderism, what is what they do? mutilate women’s breast or men sexual organs.

I am not saying the Bible is wrong saying God commanded the circumcision, but is it really what they tell us it was only because some people today who call themselves Jews do it that way?

I am pretty straight forward in my arguments and I am sorry if you disagree with my wording or logic, I know a lot of arguments by Christians, I disagree with or question, because one thing is what it is written and another thing is if it exactly meant what we see or read today.

It should be clear why I have so many questions about it, and in a way, this is more rhetorical questions, because while it is such a small tiny detail, I have known people who have circumcised their kids for the sake of doing it, so they look ‘like other kids’ or you have some people doing paganistic rituals about it to the point of it being inappropriate and passing diseases to babies and all that.

I am just talking to you like if I knew you for years, so excuse me for this long post.

I just always wondered about all this after reading that Paul verse, and all Paul letters, how he refers to the whole circumcision about it could mean more than what we know today.

And knowing how things change in few years, meaning of words, meaning of actions, how something can change so suddenly because ‘authorities’ decided to change laws, the way people do things, just knowing how evil works and twists everything and make good things bad and bad good.

Seems like something that should trassend, but not something that should be seen like a barbaric ritual, something that should be seen clearly, on the streets without you having to pull your pants down to show it, something people want to maintain and keep doing for the love to their God and not mutilating the vessel that was created on Gods image.

Why would he say in Leviticus 19:28: “28 Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you: I am the Lord”, yet, he is asking us to do something as barbaric, like I said, something you see today in the many agendas of distruction of humanity.

Like, the problem I have with it is, when will something like circumcision ends? was the promise ever finished? or it was maintained becuase of the Hebrew Law? Did God put an end to this or we should still keep mutilating our bodies like we baptize and get the eucharist? Who was this covenant or promise meant to, in that case then? Did God said “start today to do it” but why there is no word about him saying “stop, we don’t need that anymore”.

“Many Christians have not given much thought to the significance behind circumcision”, well, I think I give it too much thought, especially when I see it today, and I think it doesn’t make sense, for how God works, for how Jesus said things, just imagine, the Messiah, having his part mutilated because of Law, if Jesus was perfect, no sin, no nothing show to God his promise and works to him to be circumcised about like simple sinner mortals.

Like you said, circumcision was used for so many other things, what did that really mean in Jesus and Paul’s time? why would people believe and follow the way people do it today, mostly the ones who call themselves ‘Jews’.

I am not the typical person for sure. And little details in the bible have had more impact on me and changed my thought, my world and view in many things, which has helped me to research more and believe more.

This topic, however, has been the big question for me, becuase I know it can’t be answered, but, why would Paul word it like that to the Corinthians? why he does that in his letters, why so simple, like just something that happens and end, today you make a surgery and it takes years to heal, especially in your ‘part’ and more for adults. I know what people would say, because in a way he uses for ‘the heart’ so he is speaking in metaphors in many parts of his letters, but he never used those metaphors to speak like this and word things like this:

“Was anyone called while circumcised? Let him not become uncircumcised”

Thank you and have a good day, and don’t stop writing.

Peter Goeman

Thanks for reading the articles, Ghost Writer. I really appreciate you reading, and your encouragement. I don’t have time to interact fully with everything you’ve mentioned (I really appreciate you bringing out so many good thoughts). To zero in on 1 Cor 7:18-20, I think it is possible/probable that Paul is speaking hyperbolically there (although there were some Jews in history who did actually try to hide their circumcision, so it is possible he was being literal). I personally think it makes a little more sense for Paul to be using hyperbole, similar to how I read 1 Cor 13:1-3 (where Paul seems to use hyperbolic language there as well in reference to speaking like an angel, etc.). His point is simple: don’t seek to change your Jewishness/non-Jewishness—because that is not important in the Church.

My explanation lacks a “Wow” factor, in that it doesn’t release secret info or anything. But I think it matches with how Paul regularly is speaking in hyperbole at times.

Hope that helps!