Does Blind Bartimaeus Expose a Contradiction in the Gospels?

Throughout the history of the church, faithful men and women have confessed that the Bible is inerrant—that it is free from error in all that it affirms. When Scripture speaks, it speaks truthfully. Whatever the Bible claims, whether theological, historical, or factual, is true.

This conviction is not a later invention imposed on the text by theologians desperate to protect it. Rather, the doctrine of inerrancy arises directly from Scripture’s own claims about itself. Peter explains that “men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Pet 1:21). Paul similarly teaches that “all Scripture is God-breathed” (2 Tim 3:16). In other words, God himself stands behind the words of Scripture; he is their ultimate source.

And because God cannot lie (Titus 1:2; Heb 6:18), Scripture—being his Word—cannot err. If God is truthful, then what God inspires must likewise be true.

Yet despite this historic confession, Scripture’s integrity is frequently challenged. Skeptics and critics alike often point to alleged contradictions within the Bible, suggesting that its claims to truthfulness cannot be sustained. One such charge frequently raised concerns the healing of the blind man (or men) near Jericho, specifically the account of Bartimaeus (Matt 20:29–34; Mark 10:46–52; Luke 18:35–43). At first glance, the differences among these Gospel accounts can appear troubling. But a closer look reveals something far different.

One Blind Man or Two? Differences in Gospel Detail

Matthew records that two blind men cried out to Jesus as he was leaving Jericho. Mark, however, mentions only one blind man and identifies him by name as Bartimaeus. Luke likewise refers to one blind man, but leaves him unnamed.

Some critics attempt to press these differences into a contradiction, but such an argument misunderstands how historical accounts function. Different witnesses to the same event often emphasize different details. Selectivity is not deception; omission is not error.

Mark’s decision to name Bartimaeus likely reflects his concerns for his particular audience. Perhaps Bartimaeus was known within the early Christian community, making his name meaningful to Mark’s readers. Matthew, on the other hand, provides fuller numerical detail, noting that Bartimaeus was not alone. Luke, consistent with his narrative flow, focuses on the encounter without naming the individual.

Importantly, none of the accounts deny the presence of the others. Mark and Luke do not say only one blind man was present; they simply focus on one. Matthew’s inclusion of both men does not contradict Mark’s or Luke’s emphasis on Bartimaeus. Each author truthfully reports what serves his Spirit-guided purpose.

Rather than undermining inerrancy, these differences strengthen the historical credibility of the Gospels, demonstrating consistency with how real-life testimony works. Uniform, mechanically identical accounts would raise more suspicion, not less.

Leaving or Approaching Jericho? The Geographical Question

The more substantial challenge appears in how the Gospels describe Jesus’ location. Matthew and Mark state that Jesus healed Bartimaeus as he was leaving Jericho, while Luke says the event occurred as Jesus was approaching Jericho. At face value, these claims seem mutually exclusive. Was Jesus leaving Jericho or approaching it?

The key to resolving this tension lies in understanding Jericho’s geography during the time of Jesus.

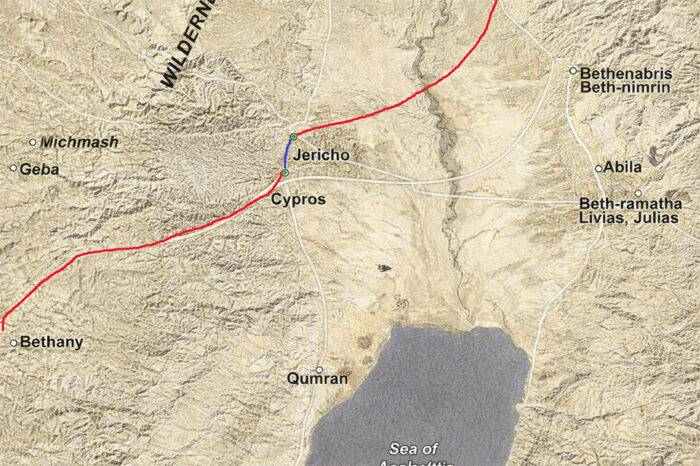

In the first century, Jericho was not a single, unified city. There were two Jerichos, separated by roughly two miles. The older, residential Jericho lay to the north and was where most people lived. To the south stood a newer, wealthier, administrative center—often called municipal Jericho—developed by the Hasmoneans and later expanded by Herod the Great.

Jesus, then, as He was traveling to Jerusalem, was walking the road between these two cities (see the following map). From one perspective, he was leaving residential Jericho. From another equally valid perspective, he was approaching municipal Jericho. Both descriptions are accurate, depending on which reference point the author emphasizes.

Luke’s narrative continues immediately with the story of Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1–10), a wealthy tax collector who almost certainly lived in the more affluent municipal Jericho. This strongly supports the idea that Jesus was nearing that southern city at the time of Bartimaeus’ healing.

Thus, Matthew, Mark, and Luke are not contradicting one another. They are describing the same event from different but compatible vantage points.

Inerrancy and the Nature of Truthful Testimony

Claims of contradiction often assume that truth requires rigid uniformity. But Scripture does not present itself as a transcript machine. It presents eyewitness testimony, shaped by authorial intent and divine, providential guidance. The Gospel writers do not flatten their accounts into identical narratives. Instead, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, they highlight different details to serve different theological and pastoral purposes—without ever compromising truth.

Far from exposing error, the blind Bartimaeus account demonstrates how careful historical reading resolves apparent tensions. The Bible proves once again to be trustworthy, coherent, and reliable. The problem, then, is not with Scripture, but with expectations imposed upon it.