Calendar, the Bible, and Ancient Israel

A calendar is a cultural convention of tracking extended time. It is internalized without much thought by a culture, but it is interesting (and important) to note that calendars have changed significantly over time. In fact, it may come as a surprise to some readers that the current method for date reckoning that Western nations use is called the Gregorian calendar, which was recently (1582 AD) put into place by Pope Gregory XIII to improve the former Julian calendar, which had been used utilized since the time of domination by the Roman Empire. The Julian calendar, named after Julius Caesar (40s BC), was largely accurate but was off by about 1 day per 100 years. Thus, Pope Gregory instituted a new calendar that would align even more precisely with the times and seasons, and would avoid having a regression (however slight it may be). So, the present calendar we use was not even being used by Martin Luther!

Not All Cultures are the Same

Most people are familiar with the Chinese New Year, or the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah. Both celebrations are indicative of the fact that there are multiple calendars in use by different cultures. The Chinese or Jewish calendars are examples of modern differences, but there are also plenty of examples of ancient calendars that are far different than ours.

Perhaps the most familiar example of an ancient calendar would be the Mayans. You may have heard about them in 2012 because the Mayan calendar supposedly predicted the end of the world. One of the interesting features of the Mayan calendar was the fact that they had 18 months of 20 days each, with an extra 5 holy days tacked on at the end of the year.

The main point is that different ancient cultures used different calendars, a point which is still relevant today in many cultures.

Major Calendar Systems in the Ancient World

Technically there are many ways to track the progress of a complete year. However, there are three main ways that ancient and modern peoples have typically kept track of dates and seasons.

The most familiar to modern readers is the solar calendar. The solar calendar organizes date and time around the position of the Sun as it relates to other stars. Our Gregorian calendar accounts for roughly 365.25 days until the sun is in the same position (and thus the same season, weather, etc.). The solar calendar is viewed by almost everyone as the most consistent and helpful calendar developed.

In contrast to the solar calendar, some ancient civilizations utilized what is known as a lunar calendar. If a solar calendar relates to the position of the sun, a lunar calendar relates primarily to the position of the moon. A lunar year is comprised of 12 months of 29.5 days a month, which results in a year of 354 days. This would mean that each year a lunar calendar loses about 11 or 12 days in comparison to a solar year. This loss of days would mean there would be pretty significant seasonal shift every 6-10 years. By way of illustration this would mean that sometimes Christmas would be in the Summer, and sometimes it would be in the Winter! To compensate for this problem, some lunar calendars would periodically add a month as a way to synchronize more closely with the seasons based on the sun’s position. A modern example of this process is the Jewish leap year, which adds a month about every 3 years.

A third example of ancient date tracking is the hybrid system. Although there were various hybrids, one of the more common was the lunistellar calendar, which is a combination of attention to the moon (lunar) and specific stars (stellar). A good example of this in the ancient world is Egypt, which utilized at least three different kinds of calendars. Egypt appears to have used a lunistellar calendar by tracking the rising and setting of Sirius, the brightest of the fixed stars. Although the years were specifically lunar (354 days), an extra month appears to have been added every 3rd year to keep the seasons roughly the same and to keep the placement of Sirius at roughly the same time.

Israel’s Ancient Calendar

Despite having significant historical record in Scripture, we do not actually have very much information on the calendar that Israel followed. We do, however, have the names of four months that the people of Israel used prior to the exile.

| Month Name | Passage |

| Abib (first month) | Exod 13:4; 23:15; 34:18; Deut 16:1 |

| Ziv (second month) | 1 Kings 6:1; 1 Kings 6:37 |

| Ethanim (seventh month) | 1 Kings 8:2 |

| Bul (eighth month) | 1 Kings 6:38 |

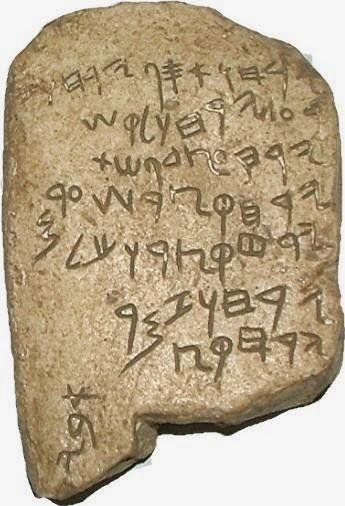

A famous archaeological find related to the ancient Israelite calendar is the Gezer Calendar, which was found in 1908 at Gezer. The Gezer Calendar contains seven lines of text which describe agricultural practices of ancient Israel. The text is written on a tablet and is dated to the 10th century BC around the time of Solomon.

The text reads as follows:

| Hebrew | Translation | Our Calendar |

| ירחו אסף | Its (two)months of harvest | September–October |

| ירחו זרע | Its (two)months of sowing | November–January |

| ירחו לקש | Its (two) months of late growth | January–March |

| ירחו עצד פשת | Its month of cutting flax | March–April |

| ירחו קצר שערם | Its month of barley harvest | April–May |

| ירח קצר וכל | Its month of harvest and measuring | May–June |

| ירחו זמר | Its (two) months of pruning | June–August |

| ירח קצ | Its month of summer fruit | August–September |

There is also a word found in the lower left corner of the Gezer Calendar, which is אבי, and most likely some sort of name (Abiy[ah], or Abi).

The fact that the Gezer Calendar tablet is on soft limestone and shows erasures has prompted many to assume it was a practice tablet for children or scribes. Regardless of its original use, it seems to show that Israel used a 12-month calendar, which was sensitive to the agricultural seasons. It may also indicate that the year was reckoned to begin in September/October, a tradition continued by the modern Hebrew calendar. This idea also has some Scriptural support, but it is complicated by the fact that Israel seems to have used two alternative methods!

Israel’s Two Calendars

As seen by the Gezer Calendar evidence, ancient Israel seems to have utilized a calendar that began in the Fall, sometime around September/October according to our reckoning. It is likely that the calendar was originally lunar (one strong reason being the word for month in Hebrew is the same word for moon, (ירח). However, because of the sensitivity to agricultural seasons (and the fact that a completely lunar 354 day calendar cannot maintain times and seasons), it is likely very early on Israel adopted the practice of adding a month every 3 years to maintain their calendar with the seasons.

However, students of Scripture note that there is at least one other calendar that apparently came in to use in Israel at some point. This is seen in multiple ways.

First, month names are different. For example, in Esther 3:7 the first month is called Nisan instead of Abib. In Esther 8:9 labels the third month, Sivan. Other post-exilic books of Scripture expand our collection of names, such as Chislev (Zech 7:1) and Elul (Neh 6:15). The month names in post-exilic books of Scripture are borrowed from Babylon, which is not surprising since Israel spent a significant portion of time there. The Babylonian month names have continued into the modern Hebrew calendar as well.

Second, the order of months also seems to be different at different points in Scripture. Already noted is the fact that Nisan is labeled as the first month, whereas Abib is labeled as the first month in the Pentateuch (cf. Exod 13:4). Both of these months begin in the Spring (March/April), but the Gezer calendar seems to indicate that the Fall begins the new year (September/October).

The idea of a Fall new year also finds support in Josephus, a 1st century Jewish historian, who writes, “This calamity happened in the six hundredth year of Noah’s government [age], in the second month, called by the Macedonians Dius, but by the Hebrews, Marchesuan [also spelled, Marheshvan]” (Antiquities, I, iii.3). The month Marheshvan is the eighth month according to the Babylonian names, but is described here as the second month.

Additionally, the Talmud also supports the idea that there was a new year that began in Tishri (b. Rosh Hashanah 11b). Tishri is the seventh month, which takes place in the Fall, but it is considered the first month here in the Talmud, and also in the modern Jewish calendar.

Edwin Thiele, famous for his work on the chronology of the kings of Israel and Judah, noted that in the biblical record Judah began their religious calendar in Nisan (Spring), but for calculating the years the king reigned they used a civil calendar (beginning in the Fall in Tishri). Alternatively, Thiele demonstrated that Israel began both their civil and religious year at the same time, at the beginning of Nisan. A chart can be helpful to visualize this.

| Order A | Order B | Babylonian Name | Ancient Name | Modern Equivalent |

| 7 | 1 | Nisan | Abib | March/April |

| 8 | 2 | Iyyar | Ziv | April/May |

| 9 | 3 | Sivan | May/June | |

| 10 | 4 | Tammuz | June/July | |

| 11 | 5 | Ab | July/August | |

| 12 | 6 | Elul | August/September | |

| 1 | 7 | Tishri | Ethanim | September/October |

| 2 | 8 | Marheshvan, or Heshvan | Bul | October/November |

| 3 | 9 | Kislev | November/December | |

| 4 | 10 | Tebet | December/January | |

| 5 | 11 | Shevat | January/February | |

| 6 | 12 | Adar | February/March |

Order A is indicative of Judah’s civil calendar, and how the Gezer calendar, Josephus, and some portions of the Talmud organize the calendar. Order B is indicative of Judah’s religious calendar, as well as Israel’s religious and civil calendar.

It is also apparent that many of the prophets utilized Order B in their reckoning of time. For example, Jeremiah notes that the ninth month was a winter month, and the king was at his winter housing with a fire (Jer 36:22). This only makes sense if you count from the Spring.

Summarizing the Evidence

We can summarize the facts and make certain estimations as follows:

- The earliest Scripture references we have (Exodus and Deuteronomy) point to Israel’s first month being in the Spring.

- In early history, Israel utilized different month names, possibly of Canaanite origin.

- At some point, apparently very early, Israel also utilized a system that began its reckoning in the Fall. This appears to be confirmed by an early 10th century archaeological find, the Gezer Calendar.

- During the divided kingdom, Judah seems to have used a different civil calendar (beginning in the Fall), while Israel used a civil and religious calendar (both beginning in the Spring).

- At some point, possibly during the exile or perhaps before, Israel adapted the Babylonian month names for its calendar.

- Israel seems to have originally used a lunar-based calendar, presumably with an extra month added every 3 years (similar to the modern Hebrew method).

- It seems that at least two calendars existed side by side in some biblical books (minimally the books of Kings and Chronicles). Perhaps similar to other ancient nations (e.g., Egypt), Israel operated with multiple calendars.

2 Comments

Duane

Mr. Goeman

Are you affiliated with the Jesuits?

sincerely,

Duane

Peter Goeman

Hi Duane,

Thanks for reading. I am not affiliated with the Jesuits.

Peter